Literature Review

Several Authors have shared their perspectives on the concept of the digital divide. Qureshi et al. (2021) view the digital divide as a component of broader social issues, emphasizing that digital inclusion is influenced by social structures, extending beyond mere access to digital technologies. Hoyos Muoz and Cardona Valencia (2023) similarly explore the social dimensions of the digital divide, focusing on its impact on social, cultural, and economic growth due to disparities in data and technology access. Kumar et al. (2023) emphasize that the digital divide is prevalent in both urban and rural areas, particularly concerning access to telecommunication infrastructure and services, with rural areas experiencing a more pronounced divide. Kumi-Yeboah et al. (2023) focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, specifically Ghana, to demonstrate how high internet service fees, limited access to digital technology, and inconsistent internet connections influenced the digital divide. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this division was most noticeable among students in higher education institutions and educators. Yoo and Jang's (2023) survey of North and South Korean migrants emphasizes the significance of a lack of digital device access and low digital literacy among some who do have device access in increasing the digital divide. But what precisely is the digital divide? Synthesizing the perspectives of these authors, two central keywords emerge: technology and inclusion. In a broader definition, the digital divide signifies the contrast between individuals who benefit from digital inclusion and those who do not. It is important to note that the digital divide is not restricted solely to developing countries; it also manifests in developed countries, despite varying percentages of occurrence.

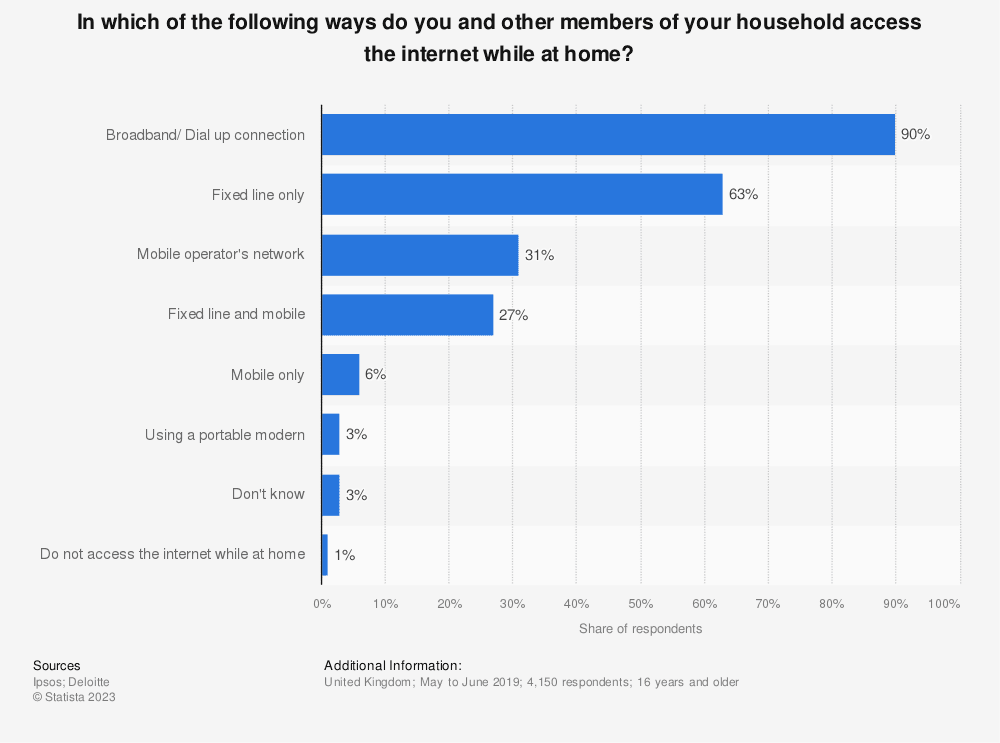

In Finland, Kemppainen et al. (2023) found that 21% of older Russian-speaking migrants lack electronic identification, which hinders their access to digital healthcare services. In the United States, Peluso (2023) investigated participants who refused to use Zelle, an online financial platform, highlighting that the digital divide may also result from individuals' reluctance to adopt certain technologies due to concerns about safety, trust, and security. Hernandez and Faith (2023) noted that despite high connectivity rates in the UK, US, and EU (95%, 93%, and 90%, respectively), challenges persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in regards to access to online services and education. They highlighted the limitations of generalized national surveys in assessing the digital divide, potentially misrepresenting the experiences of those affected. Eynon's (2023) UK-focused study interviewed digitally skilled individuals from underprivileged backgrounds, using critical realism to explore the interplay between personal choices and societal context. By critiquing one-sided policies, the research reveals digital disparities through the examination of internet activities, individual influence, and structural factors. It underscores the need for comprehensive digital inclusion strategies in the UK, addressing both personal empowerment and broader societal aspects to mitigate the impact of internet use on social inequality. The mentioned literature above indicates that the digital divide is influenced by more than just the presence of digital technology, or ICTs; people's skills and their attitudes or perceptions toward these technologies also play a significant role.

In a recent study by Carlisle et al. (2023), which encompassed 8 European countries, including the UK, and centered on the hospitality and tourism industries, it was highlighted that the digital divide is not solely about access to ICT but also encompasses a skills gap existing among those with access to these technologies. Pierce et al. (2023) also highlighted that digital exclusion encompasses more than just lacking access to technologies; it also involves the lack of involvement of the intended users. They suggested the need to accommodate diverse user needs to promote greater engagement with these technologies. Similarly, Foster (2023) examined telecommunications and infrastructure in Papua New Guinea, revealing that the digital divide isn't only confined to connectivity disparities between urban and rural users but also extends among connected users themselves. Zhao et al. (2022) conducted research involving 33 participants in China, revealing that older individuals face challenges in using healthcare information systems due to limited digital literacy. This raises the question of whether age contributes to the skill-based divide in certain contexts. Furthermore, Wilson et al. (2023) conducted interviews with individuals aged 65 and above across England, Scotland, and Wales, exploring online social technology usage. Despite access, skill deficiencies emerged as barriers to technology utilization, along with varying perceptions of these technologies. Choudrie et al. (2022) examined the impact of digital technology on older adults from ethnic minorities within the context of the digital divide. Their study, while focused on older Indian adult volunteers at a local Punjabi station, underscores the need for tailored technology-mediated learning to empower these individuals. The authors acknowledge the limitations of their small case study and suggest future research on diverse smart devices and cross-cultural differences. They emphasize the necessity for a quantitative approach to effectively measure outcomes and address the digital divide among older adults. In the realm of digital inclusion, an imbalance emerges between rural and urban children, stemming from unequal access to technology. Urban children, due to their more affluent backgrounds, enjoy superior access to technology, leading to enhanced digital literacy and better career prospects, unlike their rural counterparts (Pruet et al., 2016). The authors' study, involving 213 grade 2 students, highlights that while the Thai government equips all students with learning tablets, personal device access confers distinct advantages. This discrepancy underscores the necessity of addressing uneven educational standards and learning preferences when integrating tablet computers for educational purposes. While the research exposes positive tablet perceptions among urban and rural students, it emphasizes the imperative of understanding students' needs. Recommendations include tailored approaches to bridge gender gaps and augment technology access, ameliorating urban-rural disparities through personalized content for improved learning outcomes. Diaz-Leon et al. (2023) echo these concerns based on their study in Peru. Mathrani et al. (2023) uncovered gender-based digital inclusion disparities in five developing South Asian countries, particularly underscoring challenges faced by female children. These discrepancies became more apparent during the pandemic, when remote learning became crucial. This situation may reinforce the notion that technology is predominantly associated with males rather than females. Joshi et al. (2023) believe that introducing digital innovations could worsen disparities, particularly affecting women and marginalized communities. Ali et al. (2023) highlighted issues of misinformation and panic buying triggered by social media during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Despite the digital divide, those facing digital exclusion might not be impacted by online issues, leading some to use this as an excuse for disengagement. The literature above may suggest that certain barriers and forms of divide are more prevalent among specific demographics. However, this doesn't negate the presence of varying degrees of divide across all demographics.

Alfredsson et al. (2020) focused on adolescents and young adults with intellectual disabilities, revealing that possessing internet-enabled devices doesn't always equate to internet connectivity, especially due to high internet service costs. They stressed considering varied aspects of access and usage, including devices, connections, and adaptative strategies, to address digital inclusion challenges among young individuals with intellectual disabilities. Despite involving only 15 participants, this study provides valuable insights into how the digital divide can impact young people. Shafari et al.'s (2021) research highlighted older adults' perceptions of teenagers' excessive reliance on devices and social media, which may trigger social anxieties like the fear of missing out, impacting mental well-being. Consequently, this perception may prompt parents or guardians to impose restrictions on their children's technological usage, especially concerning social media. While moderation is important, excessive restrictions might inadvertently contribute to digital exclusion and exacerbate the digital divide between adolescents and their peers. The study, involving 35 group discussions with 115 Canadian teenagers aged 13 to 19, indicated their awareness of device addiction, excessive use risks, and security concerns. They suggested this addiction could extend to adults and society. However, it remains to be determined whether this awareness is genuine or merely expressed. Barrantes and Vargas's study (2019) in Buenos Aires, Lima, and Guatemala City found a digital divide favoring younger adults, yet older adults were more inclined to use social media professionally, online banking, and government services. However, Flynn's study (2022) demonstrated younger individuals' role in bridging the digital divide by aiding older generations with digital technology adoption. This Irish survey of 248 young adults showcased how these efforts facilitated digital communication skills development among older family members, recording a 90% success rate for independent communication during and after lockdown periods.

Morse et al. (2022), investigating a flipped learning classroom where students watched teacher videos at home before practical work in class, emphasized that digital divide-affected children, particularly those in rural settings, may face challenges in fully engaging with learning activities. This underscores how children growing up in digitally divided communities could struggle to keep pace with their peers, potentially impacting their future access to opportunities. Wallengren et al. (2023), studying how social educators adapted online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, underscored the need to address digital inequality to ensure students fully benefit from such online learning platforms.

UK methods of accessing the internet from home in 2019 before the Pandemic

In conclusion, the literature reviewed underscores the all-round nature of the digital divide, extending beyond mere access to technology. The authors emphasize that social structures, skills, attitudes, and inequalities contribute to this divide, with implications spanning education, economic progress, and social integration. The literature review highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic unveiled pre-existing levels of the digital divide in specific countries and communities. When applying these insights to the Droflas community, it becomes evident that distinct challenges may emerge, encompassing affordability, dependable internet access, and digital literacy. Tailored strategies become imperative, particularly for marginalized groups and older individuals. The case study of Sarah shows that she is at the first level of the digital divide due to her limited income hindering access to digital technology, which in turn extends to affect her children. It is important to note that Sarah also faces a deficiency in the skills necessary to effectively utilize these technologies.